Orthographic Current Shorthand

- The Alphabet

- General Principles

- Vowels

- Arbitraries

- Consonants

- Projection Indicates Articulation

- Form Indicates Quality

- Consonants Requiring Special Notice

- Consonant-Groups

- nt, mp, nk; nd, mb

- pt, kt; bt, g(h)t; ft, ct, tht

- pf, ck

- s before

- s after

- s after vowels

- les, res

- loop z and cross-loop s after curved-foot consonants

- -ses

- back-hook for final s

- -hs, -qs, -ques

- thr, thw

- forward-ring w

- obvious ligatures

- raised short consonant beginning a consonant group

- other ways to form ligatures

- Rising Consonants

- List of Characters

- Contraction

- Specimens

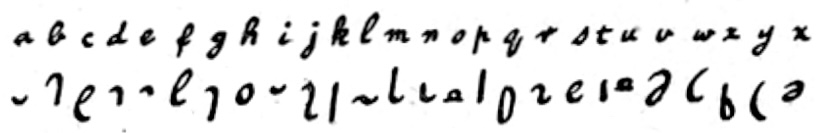

The Alphabet

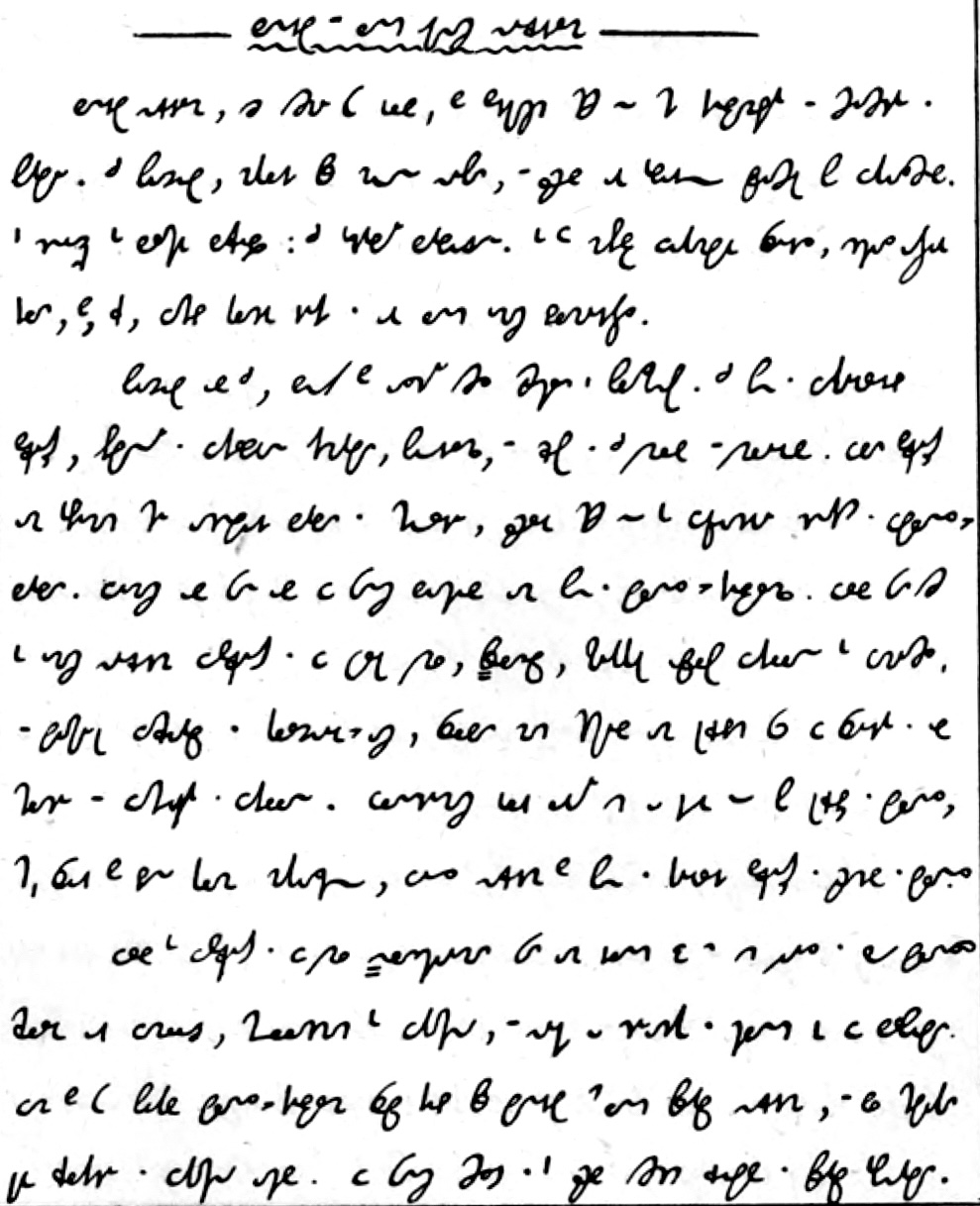

The following is the elementary alphabet of Orthographic Current Shorthand:

General Principles

Consonants are expressed by full-sized characters, such as

s,

s,

t,

vowels by small characters, as in

t,

vowels by small characters, as in

sit.

i is a ‘high-mid’ vowel.

Some vowels are written at the ‘low-mid’ level, such as o,

as in

sit.

i is a ‘high-mid’ vowel.

Some vowels are written at the ‘low-mid’ level, such as o,

as in

not.

not.

The only consonant that is written small is L,

expressed by low-mid  before vowels,

by high-mid

before vowels,

by high-mid  after vowels,

as in

after vowels,

as in

lot,

lot,

salt.

salt.

The other consonants are distinguished by their ‘projection’.

‘Short’ consonants, such as

,

,

,

,

,

do not project at all.

The ‘long’ consonants are either

‘high,’ such as

,

do not project at all.

The ‘long’ consonants are either

‘high,’ such as

b,

‘low,’ such as

b,

‘low,’ such as

c,

or tall, such as

c,

or tall, such as

tt.

Examples:

tt.

Examples:

bin,

bin,

cat,

cat,  cab,

cab,  bitten.

bitten.

If the vowel before or after a consonant is not

written, the stroke is used to show the presence of a vowel — generally e — as in

else.

else.

When two consonants come together without any vowel between,

forming a ‘consonant-group,’

they are, if possible, joined together without any stroke, as in

,

where ls forms a ‘ligature.’

,

where ls forms a ‘ligature.’

If this cannot be done,

they are crowded together,

or written detached and close together,

as in

,

,

Etna,

or else ‘grafted’ together,

as in

Etna,

or else ‘grafted’ together,

as in

Camden.

Camden.

But many consonant-groups are expressed by simple characters,

such as

th

in

th

in

thin.

Such groups as st, ts, are expressed by joining the loop of the s directly on to the t, as in

thin.

Such groups as st, ts, are expressed by joining the loop of the s directly on to the t, as in

state

state

lets.

lets.

A consonant-character standing alone is used as a ‘sign,’

that is, a contraction of some special word,

or of several words pronounced alike.

Thus

= to, too, two,

= to, too, two,

= the,

which is however generally joined on to the following word, as in

= the,

which is however generally joined on to the following word, as in

the cat.

the cat.

Some signs are made by writing ‘in position’,

that is, raised or lowered above or below the line of writing.

Thus raised

= it,

lowered

= it,

lowered

= than.

= than.

Vowels

-

e, ee.

e, ee.

let;

let;

seen.

Most medial (in the interior of a word) unaccented vowels may also be expressed by the short stroke:

seen.

Most medial (in the interior of a word) unaccented vowels may also be expressed by the short stroke:

canal,

canal,

singing.

singing. -

i.

i.

imitate,

or, using the short stroke for the medial i,

imitate,

or, using the short stroke for the medial i,

.

. -

a.

a.

a man.

When convenient, may be written inside the curve of some consonants:

a man.

When convenient, may be written inside the curve of some consonants:

vain.

vain. -

y.

y.

gypsy.

The shorter i may generally be written instead:

gypsy.

The shorter i may generally be written instead:

“gipsi,”

“gipsi,”

city (literally ‘citi’),

city (literally ‘citi’),

day (literally ‘dai’).

day (literally ‘dai’). -

œ.

œ.

phœnix,

or, using the short stroke for the medial i,

phœnix,

or, using the short stroke for the medial i,

.

. -

e, ee.

These characters are only occasionally written instead of the stroke, as in

e, ee.

These characters are only occasionally written instead of the stroke, as in

true.

Full e is often more distinct finally

(at the end of a word)

than the stroke, as in

true.

Full e is often more distinct finally

(at the end of a word)

than the stroke, as in

fine

distinguished from

fine

distinguished from

fin.

Full ee is sometimes more distinct than the long stroke.

[No example is provided.]

fin.

Full ee is sometimes more distinct than the long stroke.

[No example is provided.] -

æ.

æ.

Cæsar.

Cæsar. -

u.

The second form is used when u is written detached, to distinguish it from

u.

The second form is used when u is written detached, to distinguish it from

r.

r.

-

o.

o.

soul.

Detached

soul.

Detached  = o!

= o! -

w.

Used only to express w after a vowel, as in

w.

Used only to express w after a vowel, as in

saw,

saw,

now.

In all familiar words u may be substituted:

now.

In all familiar words u may be substituted:

‘sau,’

‘sau,’

‘nou.’

‘nou.’

Lengthening

Lengthening a vowel-character implies preceding e:

-

ei.

ei.

vein.

vein. -

ea.

ea.

,

,  easy.

easy. -

ey.

ey.

they.

In most cases ei may be written instead:

they.

In most cases ei may be written instead:

.

. -

eu.

eu.

Europe.

Europe. -

eo.

eo.

people.

people. -

ew.

ew.

Carew.

In most words eu may be substituted:

Carew.

In most words eu may be substituted:

new (literally “neu”).

new (literally “neu”).

ie, oa

-

is used to express ie, as in

is used to express ie, as in

piece.

In the combination ieu the i is written separately,

and the e is implied by lengthened u:

piece.

In the combination ieu the i is written separately,

and the e is implied by lengthened u:

lieutenant.

lieutenant. -

may be used to express oa:

may be used to express oa:

oatmeal.

oatmeal.

Detaching

In the combination aa the two vowels

must be written detached:

Isaac.

So also in such combinations as

Isaac.

So also in such combinations as

lying.

lying.

When a low vowel has to be detached after a high one,

it is written immediately under the high one:

guard.

guard.

Arbitraries

The following arbitrary marks, written like vowels, are used to express certain very common words:

-

and.

Compare the use of the hyphen (-) in ordinary writing.

and.

Compare the use of the hyphen (-) in ordinary writing. -

or.

or. -

of.

of.

Examples:

now and then;

now and then;

now or never;

now or never;

a piece of cake.

a piece of cake.

Consonants

Projection Indicates Articulation

The projection of a consonant-character shows the place in the mouth where the sound it generally represents is formed.

Short = Point

The point (tongue-point) consonants are written short:

t,

t,

d,

d,

n;

n; s,

s,

z;

z; th;

th; r.

r.

Examples:

detain,

detain, seize,

seize, the rat.

the rat.

Signs:

= to(o), two;

= to(o), two;

= it

= it = twice;

= twice;

= its, it is (it’s)

= its, it is (it’s) = on;

= on;

= in;

= in;

= than

= than = is

= is = the, thee;

= the, thee;

= this

= this

High = Lip

The lip-consonants are written high:

p,

p,

b,

b,

m;

m; f,

f,

v;

v; w (as in we),

w (as in we),

ph.

ph.

Examples:

problem,

problem, five,

five, wolf,

wolf,

sylph.

sylph.

Signs:

= but

= but = for, fore, four

= for, fore, four = won, one

= won, one

Low = Back

The back-consonants are written low:

k,

k,

c,

c,

g,

g,

ng;

ng; qu (= kw),

qu (= kw),

x (= ks).

x (= ks).

So also:

y (as in you)

y (as in you)

j, and

j, and

sh.

sh.

because they are formed further back in the mouth than the point-consonants.

Examples:

-

king,

king,  cook,

cook,  going

going -

queen,

queen,  six

six -

rejoice,

rejoice,  youngish

youngish

Signs:

= because

= because = again

= again = quite

= quite = you

= you

Tall = Doubled Point

The tall consonants indicate doubling of the corresponding short or small ones:

tt,

tt,

dd,

dd,

nn;

nn; ss,

ss,

zz;

zz; rr,

rr,

ll.

ll.

Examples:

-

ditto,

ditto,  middle,

middle,  penny

penny -

less,

less,  buzz

buzz -

sorry,

sorry,  tell,

tell,  silly

silly

Form Indicates Quality

The other classes under which consonants fall are partly indicated by their form:

| hard: |  t t |

p p |

k k |

s s |

f f |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| soft: |  d d |

b b |

g g |

z z |

v v |

| nasal: |  n n |

m m |

ng ng |

Consonants Requiring Special Notice

Some of the consonants require special notice.

H

h is generally expressed by the low stroke when initial (at the beginning of a word):  hat.

hat.

Non-initial h is expressed by

as in

as in

ah!,

the stroke being drawn through the character, as with

ah!,

the stroke being drawn through the character, as with

qu,

when convenient:

qu,

when convenient:

behalf.

behalf.

This character also forms part of the ligatures:

kh as in

kh as in

khan,

khan, ch as in

ch as in

cheque,

cheque, gh as in

gh as in

laugh,

laugh, rh as in

rh as in

rhyme,

rhyme, wh as in

wh as in

when.

when.

Medial h may be expressed by drawing a stroke through the preceding character, as in

,

,  behave.

behave.

Signs:

= how

= how

L

L has been partly explained under ‘General Principles’.

Long high

= eel,

long low

= eel,

long low

= lee,

as in

= lee,

as in

feel,

feel,

bleed,

the stroke being prefixed to initial eel and added to final lee:

bleed,

the stroke being prefixed to initial eel and added to final lee:

eel,

eel,

Lee,

Lee,

glee.

glee.

After a long vowel

the L may

be lengthened instead of the vowel, as in

veil.

veil.

The stroke before low L must be written under the line:

elect.

elect.

L is also expressed by the upright

,

which always implies a following vowel,

expressing ‑le when final:

,

which always implies a following vowel,

expressing ‑le when final:

mile.

It is necessary when vowel + L is followed by a low vowel, as in

mile.

It is necessary when vowel + L is followed by a low vowel, as in

felon,

unless a break

(

felon,

unless a break

( fel/on)

or contraction

(

fel/on)

or contraction

( feln)

is made.

feln)

is made.

In the combination consonant + L + vowel,

the L may be implied by lengthening the stroke before the vowel:

slip,

slip,

float.

Hence initial

float.

Hence initial

may be used to express loa, as in

may be used to express loa, as in

load.

load.

Signs:

= all

= all = always

= always = below

= below

R

r when final or followed by a consonant is expressed by

,

which is run on to t, n, etc.:

,

which is run on to t, n, etc.:

terror,

terror,

word,

word,

heart,

heart,

burn.

burn.

Before such consonants as s it may be written as an upward loop run on to the consonant:

curse,

curse,

force.

force.

Final

always implies a following vowel:

always implies a following vowel:

here.

here.

r is added to straight-stem consonants in the form of a ‘back ring,’ as in

tr:

tr:

true,

true,

pride,

pride,

green,

green,

street.

street.

Consonants

ending in rising loops add r as in

fr:

fr:

fruit:

fruit:

phrase,

phrase,

Nimrod,

Nimrod,

creature.

creature.

r is simply crowded on after down-loop consonants such as

sh:

sh:

shrill.

shrill.

nr is best written grafted, as in

Henry.

Henry.

Signs:

= her

= her = perhaps

= perhaps = from

= from

Consonant-Groups

As we have seen, many consonant-groups are expressed by simple characters, not only when they express simple sounds, such as sh, but also when they express compound sounds, such as x. The following consonant-groups are also expressed by simple characters:

nt, mp, nk; nd, mb

nt, mp, nk;

nt, mp, nk;

nd, mb.

nd, mb.

Examples:

tent,

tent,

lamp,

lamp,

ink;

ink; find,

find,

number.

number.

Signs:

= unto

= unto = into

= into = under

= under

pt, kt; bt, g(h)t; ft, ct, tht

pt,

pt,

kt;

kt; bt,

bt,

gt (but more often used for ght);

gt (but more often used for ght); ft,

ft,

ct,

ct,

tht.

tht.

Examples:

adapt;

adapt; debt,

debt,

bright.

bright. left,

left,

fact.

fact.

Signs:

= about

= about = against

= against = that

= that

pf, ck

pf

pf ck

ck

Examples:

Pfeiffer

Pfeiffer cackle

cackle

s before

s is prefixed to another consonant by means of a loop.

Examples:

- As a high anti-clockwise loop before the straight stem consonants:

st as in

st as in

stand

stand sp as in

sp as in

spread

spread sk as in

sk as in

task

task

- As a high clockwise loop before b and w:

sb as in

sb as in

husband

husband sw as in

sw as in

swift

swift

- As a low anti-clockwise loop before most consonants:

sn as in

sn as in

snow

snow sm as in

sm as in

smoke

smoke sf as in

sf as in

satisfy

satisfy sc as in

sc as in

scale

scale squ as in

squ as in

squint

squint sph as in

sph as in

sphere

sphere

Signs:

= some, sum

= some, sum

s after

It is also added by a loop in:

ts as in

ts as in

sits

sits ps as in

ps as in

copse

copse ks

ks tts as in

tts as in

butts

butts pts as in

pts as in

adopts

adopts ths as in

ths as in

paths

paths

and also:

ls as in

ls as in

details

details lls as in

lls as in

fills

fills nds as in

nds as in

sends

sends nts etc. as in

nts etc. as in

lamps, and

lamps, and rs as in

rs as in

letters.

letters.

Signs:

= twice

= twice

s after vowels

s may be looped on after vowels also,

especially oa, as in

boas.

boas.

les, res

les as in

les as in

miles

miles res as in

res as in

fares

fares

loop z and cross-loop s after curved-foot consonants

Looping up such a character as

n adds

n adds

z

as in

z

as in

nz,

the ‘cross-loop’ being used to add

nz,

the ‘cross-loop’ being used to add

s

as in

s

as in

ns.

ns.

Examples:

bronze

bronze sins

sins seems

seems sings

sings loafs

loafs

-ses

Cross-looping

s,

s,

ss

adds -es, as in:

ss

adds -es, as in:

loses

loses misses.

misses.

ns

may be made into nses by looping up the cross-stroke:

ns

may be made into nses by looping up the cross-stroke:

,

,  sense, -s.

sense, -s.

back-hook for final s

When the loop is not convenient, final s is added by means of a ‘back-hook’ or any convenient hook that is not liable to be taken for a vowel:

reads

reads cabs

cabs lights

lights ,

,  laughs

laughs ,

,  ,

,  tests.

tests.

-hs, -qs, -ques

Final hs, qs, ques are written:

-hs as in

-hs as in

the Shah’s turban

the Shah’s turban -q(ue)s as in

-q(ue)s as in

M. Le Coq’s clothes

M. Le Coq’s clothes

thr, thw

- thr is expressed by

as there is no sr in English:

as there is no sr in English:

thrice

thrice - So also thw is expressed by

:

:

thwart

thwart

- Note that this is distinct from

sw,

which uses the high clockwise loop to represent s.

sw,

which uses the high clockwise loop to represent s.

- Note that this is distinct from

forward-ring w

w is generally added by means of the ‘forward ring’, which is written either upwards or downwards as is most convenient:

twitter

twitter dwell

dwell

Signs:

= between

= between

obvious ligatures

There are many ligatures which do not require explanation, such as

dz as in

dz as in

adze

adze pph as in

pph as in

sapphire

sapphire

Signs:

bv = above

bv = above

raised short consonant beginning a consonant group

When a short consonant begins a consonant-group, it may be written raised, implying that there is no vowel between:

,

,  nonsense

nonsense punctual

punctual æsthetic.

æsthetic.

It is often convenient to write

ntr etc in this way, as in

entry =

entry =  ,

mpr being written

,

mpr being written

, as in

, as in

empress.

empress.

other ways to form ligatures

Some ligatures may be made by joining on below the line:  depth.

depth.

In other cases, crowding, detaching, and grafting must be employed:

crimson,

crimson,

songster,

songster,

nymph ;

nymph ; suffer,

suffer,

upper ;

upper ; christen,

christen,

actress.

actress.

Rising Consonants

Some of the consonants are written upwards as well as downwards,

so as to avoid connecting-strokes.

When these ‘risers’ are written detached,

we graft them on to a horizontal stroke, thus

= rising b.

Most of them are written only finally,

and are employed chiefly in contractions.

= rising b.

Most of them are written only finally,

and are employed chiefly in contractions.

rising th as in

rising th as in

,

,  tenth, -s

tenth, -s ,

,

rising p, b

rising p, b rising f as in

rising f as in

rising v as in

rising v as in

;

;

,

,  love, -s.

This character is used more freely than the other risers.

love, -s.

This character is used more freely than the other risers.

Signs:

= although

= although = with

= with

List of Characters

Of some of the ligatures only a few examples are given under the modifying element – ts under s etc.)

- a:

.

. -

æ:

.

. - b:

.

.  .

. -

bt:

.

. - c:

.

. - ch:

.

. - chr:

.

. - ck:

.

. - cr:

.

. - ct:

.

. -

ctr:

.

. - d:

.

. -

dd:

.

. - e:

.

. - ea:

.

. - ee:

.

. - eel:

.

. - ei:

.

.

- eo:

.

. - eu:

.

. - ew:

.

. -

ey:

.

. - f:

.

.  .

. -

ft:

.

. - g:

.

. - gh:

.

. -

ght:

.

. -

h:

.

.  beh-.

beh-. - i:

.

. -

ie:

.

. - j:

.

. -

k:

.

. - l:

.

.  sla.

sla. - -le:

-

lee:

- m:

- mb:

-

mp:

- n:

- nd:

- ng:

.

. - nk:

.

. - nn:

.

. - nr:

-

nt:

- o:

- oa:

-

œ:

- p:

.

.  .

. - pf:

.

. - ph:

.

. - pt:

.

.

-

q(u):

.

. - r:

.

.

tr.

tr.  fr.

fr.

- rh:

.

. -

rr:

.

. - s:

.

.

st.

st.

sw.

sw.

sn.

sn.

ts.

ts.

ds.

ds.

,

,  ns.

ns.

- sh:

.

.

- sph:

.

. - ss:

.

. -

sw:

.

. -

t:

.

. - th:

.

.  .

. - thr:

.

. -

thw:

.

. -

tt:

.

. - u:

.

.

-

v:

.

.  .

. - w:

;

;

.

.

tw.

tw.

-

wh:

.

. -

x:

.

. -

y:

;

;

.

. - z:

.

.

nz.

nz.

- zz:

.

.

Contraction

The extent to which contraction may be carried varies under different circumstances. It is evident that familiar words may be more safely contracted than unfamiliar ones, altho even these may be contracted when they are repeated.

The Three Principles

In contracting there are three main principles to be observed:

-

To keep the most sonorous and distinct elements of a word, that is, the accented vowels and the syllables that contain them, as when we contract phótograph into phot-gr-ph

or phot-g-ph

or phot-g-ph

,

photográphic into

ph-t-gra(phi)c

,

photográphic into

ph-t-gra(phi)c

.

. -

To keep, if possible, the beginning and end of the contracted word, as in the last example.

-

To keep the distinctive elements of a word, that is, those sounds or letters which distinguish it from other words with which it might be confounded ; thus the i of sit is distinctive, because it distinguishes sit from sat and set, and should therefore be written in full, while two such words as quality and quantity are distinguished solely by their medial consonants l and nt:

,

,

.

.

The most obvious method of contraction is the omission of silent letters, that is, letters which are neither sounded themselves nor modify the sounds of other letters, as in the following examples:

bread,

bread,ple.jpg) people,

people, edge,

edge, eye,

eye, double,

double, mourn ;

mourn ; stuff,

stuff, suppose,

suppose, ghost,

ghost, lamb,

lamb, foreign,

foreign, ,

,

knowledge.

knowledge.

The substitution of a phonetic for an unphonetic spelling often shortens writing or makes it easier.

Thus

it is convenient to write f for ph and gh in such words as

sphere,

sphere,

phlegm,

phlegm,

enough.

So also k and s may be written instead of c (ch), as in

enough.

So also k and s may be written instead of c (ch), as in

secret,

secret,

school,

school,

success.

success.

h should be dropped in all words which drop it when unaccented, such as

him, ’im  .

As h is dropped in all words in vulgar speech without causing confusion,

it may be dropped in writing in all familiar words.

It is especially convenient to drop it when not initial, as in

.

As h is dropped in all words in vulgar speech without causing confusion,

it may be dropped in writing in all familiar words.

It is especially convenient to drop it when not initial, as in

abhor,

abhor,

apprehend,

where the e is written in full to show that it is accented.

apprehend,

where the e is written in full to show that it is accented.

Any vowel or vowel-group may be expressed by the short stroke

if the consonant-outline is distinctive enough, as in

chasm,

chasm,

pseudonym,

especially in unaccented syllables, as in

pseudonym,

especially in unaccented syllables, as in

honour.

honour.

When unaccented vowels are dropped between consonants,

these may often be joined together into ligatures, as in

credulous,

credulous,

shilling,

shilling,

separate,

separate,

opposite.

opposite.

er, ir, ur final or before consonants all have

the same sound, as in serve, sir, fur ;

hence they can all be written alike with the simple stroke:

serve,

serve,

sir,

sir,

fur.

This allows us to shorten ier final or before a consonant into ir:

fur.

This allows us to shorten ier final or before a consonant into ir:

fierce.

fierce.

A further step in contraction is the omission of sounding letters, whenever this can be done without causing confusion:—

Double consonants may often be written single, as in

beggar,

beggar,

er.jpg) upper,

k being written for ck, as in

upper,

k being written for ck, as in

,

,

pick, -ing.

pick, -ing.

Inconvenient consonant-joins may often be avoided by omitting one of the consonants — either the one that is least easy to write or is least distinctive:

absent

[

absent

[ assent],

assent],

admire,

admire,

object ;

object ;

attempt,

attempt,

tincture,

tincture,

,

,

relinquish.

relinquish.

magnificent ;

magnificent ;

omnipotent,

omnipotent,

pamphlet ;

pamphlet ;

nonchalant.

nonchalant.

r may often be omitted,

especially in unaccented syllables:

prepare,

prepare,

telegraph.

It is especially convenient to write ct for ctr, as in

telegraph.

It is especially convenient to write ct for ctr, as in

electric.

r may often be omitted before a

consonant, as in

electric.

r may often be omitted before a

consonant, as in

southern.

southern.

mb, mp, nd, nt may often be shortened to m, n:

resemble,

resemble,

important ;

important ;

random,

random,

interest.

So also — with dropping of r as well —

interest.

So also — with dropping of r as well —

introduce.

mbr, mpr may be shortened to mr:

introduce.

mbr, mpr may be shortened to mr:

Cambridge,

Cambridge,

emperor.

emperor.

Longer words may often be shortened by whole syllables:—

Thus -ate may be dropped in many verbs, as in

abdicate,

abdicate,

.jpg) imitate,

imitate,

ventilate.

ventilate.

Such endings as -alogy may be contracted by writing only their beginning and end with a distinctive consonant between,

analogy, for instance, being shortened to

.

Other examples are:

.

Other examples are:

democracy,

democracy,

,

,

theology,

theology,

geography,

geography,

philosophy,

philosophy,

economy,

economy,

misanthropy.

misanthropy.

Final c is so rare except in words ending in -ic

that most of these words can be contracted by joining the c on to the next preceding accented vowel,

omitting the intervening consonants:

physic,

physic,

photographic,

photographic,

misanthropic.

The ending

-cal may be expressed by adding low L, as in

misanthropic.

The ending

-cal may be expressed by adding low L, as in

physical,

physical,

logical [

logical [ local].

The -al may be omitted in such words as

local].

The -al may be omitted in such words as

practical,

practical,

theatrical.

Other derivative syllables may be added, as in

theatrical.

Other derivative syllables may be added, as in

physician.

physician.

As v never occurs finally in English,

final

may be used to imply contraction, as in

may be used to imply contraction, as in

positive,

positive,

imperative.

imperative.

As x is very rare initially,

initial vowels can always be omitted before it:

axiom,

axiom,

excellent,

excellent,

extravagant,

extravagant,

extraordinary.

extraordinary.

So also cata-, cate- may be contracted to ct-, preter- to pt-, trans- to ts-:

catalogue,

catalogue,  category ;

category ; preternatural ;

preternatural ; ,

,  translate.

translate.

sub- may be contracted to sb:

subject,

subject, substance, and, with contraction of the body of the word,

substance, and, with contraction of the body of the word,  ;

; substantial.

substantial.

In this, as in other prefixes and endings, the stroke between it and the body of the word does not necessarily imply a vowel.

So, again, un- may be shortened to u-, uni- to ui-:

- u(n)-

unseen

unseen unkind

unkind unhealthy

unhealthy

- u(n)i-

,

,  uniform

uniform universal

universal

When final y is written i,

full final y may be used to imply the endings -ety, -ity, as in

variety,

variety,

deity,

and, with further contraction,

deity,

and, with further contraction,

dignity,

dignity,

reality,

reality,

authority.

The y must be kept when an inflection is added:

authority.

The y must be kept when an inflection is added:

abilities.

abilities.

As ng does not occur initially,

initial

may be utilized to express

con-, com(m)-,

as in

may be utilized to express

con-, com(m)-,

as in

contend,

contend,

,

,

complex,

complex,

common.

So also:

common.

So also:

= contra-

as in

= contra-

as in

contradict,

contradict, = contro-

as in

= contro-

as in

controvert,

controvert, = counter-

as in

= counter-

as in

counterfeit.

counterfeit.

Characters which are not required in ordinary writing may be used as contractions of prefixes and endings:—

Thus may be utilized:

to express Saint (St.) as in

to express Saint (St.) as in

,

,  St. John,

St. John,

St. Paul’s,

St. Paul’s, to express super- as in

to express super- as in

superfluous,

superfluous, to express circum- as in

to express circum- as in

,

,  circumstance, -stantial.

circumstance, -stantial.

Final  without an up-stroke may be used to express

-able, -ible etc, as in

without an up-stroke may be used to express

-able, -ible etc, as in

peaceable,

peaceable,

terrible,

and

terrible,

and

to express -bility, as in

to express -bility, as in

excitability,

excitability,

volubility.

volubility.

,

=

,

=  n with the hook turned back,

may be used to express:

n with the hook turned back,

may be used to express:

- -ion as in

union

union - -s(s)ion as in

vision and

vision and

mission

mission - -tion as in

nation.

nation.

Preceding lip consonants are implied by writing the character high, like a p or m:

adoption

adoption presumption.

presumption.

It is written low to imply a preceding c:

action

action junction.

junction.

The tall form may be utilised to express -ntion:

mention.

mention.

s may be hooked on, and other endings added:

unions

unions actions

actions nationality.

nationality.

is similarly used as a contraction of

-eous, -ious, -uous,

so as to avoid breaks:

is similarly used as a contraction of

-eous, -ious, -uous,

so as to avoid breaks:

gorgeous

gorgeous tedious

tedious ,

,

sumptuous

sumptuous

If the accented vowel of the word is written, intervening consonants may be omitted:

sagacious.

sagacious.

—

a closed-up

—

a closed-up  m —

may be used to express

the endings -man, -men

(which are pronounced alike)

so as to avoid inconvenient consonant-joinings, as in:

m —

may be used to express

the endings -man, -men

(which are pronounced alike)

so as to avoid inconvenient consonant-joinings, as in:

,

,

gentle-man, -men

gentle-man, -men gentle-man’s, -men’s

gentle-man’s, -men’s Englishman.

Englishman.

Another way of contracting prefixes and endings is by the use of position:

may be joined on to express not only in-,

but also im- and the like-sounding en-, em-:

may be joined on to express not only in-,

but also im- and the like-sounding en-, em-:

intend

intend entire

entire impress

impress employ

employ enthusiasm

enthusiasm enthusiastic

enthusiastic- imm- is best written

:

:  immediate

immediate

= dis-, des-,

the s being written instead of d for the sake of easier joining:

= dis-, des-,

the s being written instead of d for the sake of easier joining:

dissent, descent

dissent, descent distant

distant display

display

-ly:

-ly:

manly

manly only

only really

really terribly

terribly ungentlemanly

ungentlemanly

The following endings are contracted for the same reason as -man, but by position:

-ward(s), the s being often dropped:

-ward(s), the s being often dropped:

,

,  forward, -s

forward, -s towards

towards

-ful:

-ful:

useful

useful successfully

successfully

-ness:

-ness:

hardness

hardness usefulness

usefulness

-ment, -mentary, -mental, -mentality:

-ment, -mentary, -mental, -mentality:

,

,  agreement

agreement rudimentary

rudimentary fundamental

fundamental instrumentality.

instrumentality.

Word-Omission

The possessive pronouns my etc. may almost always be omitted before self and own:

I saw it myself

I saw it myself I saw it with my own eyes

I saw it with my own eyes

to before verbs may generally be omitted, as in:

you ought to know what to do

you ought to know what to do

Many other subordinate words may be omitted in quick writing, such as the, a, of.

Signs

Most signs are formed by giving fixed values to isolated consonants or consonant-groups.

The raised signs all contain the vowel i:

= it etc.

Some of the contractions here given fall under the general rules already given.

= it etc.

Some of the contractions here given fall under the general rules already given.

This list includes only the most necessary

signs;

but others may be formed at pleasure, such as

difficult,

difficult,

difficulty,

difficulty,

different,

different,

enough,

enough,

full,

full,

great,

great,

possible,

possible,

short,

short,

.jpg) true.

true.

The ordinary long-hand contractions may of course be used in shorthand as well:

tho(ugh),

tho(ugh),

thro,

thro,

Mr.,

Mr.,

Mrs.,

Mrs.,

Messrs.

Messrs.

A

- about

- above

- after

- afterwards

- again

- against

- all

- almost

- already

- also

- although

- altogether

- always

- among

- amongst

- and

- away

B

- because

- before

- behind

- below

- beneath

- between

- beyond

- both

- but

E

- either

F

- for(e), four

- fo(u)rth

- from

H

- had

- has

- have

- he

- her, hers

,

,

- him

- his

- how

I

- in

- into

- is

- it

N

- neither

- nevertheless

- nothing

- notwithstanding

O

- of

- off

- often, orphan

- on

- one, won

- or

- other

- our, hour

- over

P

- perhaps

Q

- quite

R

- rather

S

- self

- selves

- some, sum

- something

- sometimes

T

- than

- that

- the(e)

- therefore

- this

- till

- to(o)

- together

- twice

- two

U

- under

- underneath

- unless

- until

- unto

W

- wherefore

- whether, weather

- with

- without

Y

- you

- your

- yours

Free Contractions

The high stroke

stands for any word.

stands for any word.

stands for any group of words.

These marks may be made more definite by prefixing the initial letter of the single word,

or the initial letters of the chief words of the group,

all the characters being joined together.

Thus laudanum, stalactite may be expressed by

stands for any group of words.

These marks may be made more definite by prefixing the initial letter of the single word,

or the initial letters of the chief words of the group,

all the characters being joined together.

Thus laudanum, stalactite may be expressed by

,

,

respectively,

or, if the context is clear enough, by simple

respectively,

or, if the context is clear enough, by simple

;

and United States may be expressed by

;

and United States may be expressed by

,

,

,

or by

,

or by

alone.

alone.

A more accurate method of free contraction is writing the initial and final letters or letter-groups of a word detached and close together; thus

= laudanum,

or any other word beginning with L and ending in M,

= laudanum,

or any other word beginning with L and ending in M, ,

,

= stalactites etc,

= stalactites etc, = mahogany etc.

= mahogany etc.

When convenient, a final consonant may be written across the up-stroke of an initial consonant, as in

= satrap etc.

= satrap etc.

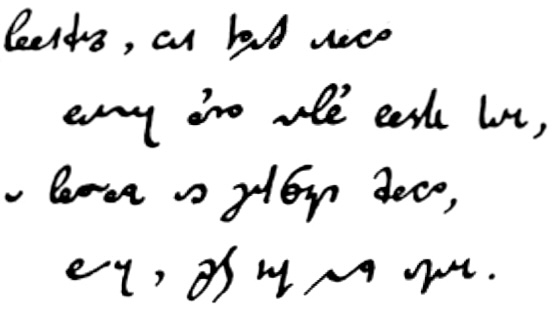

Specimens

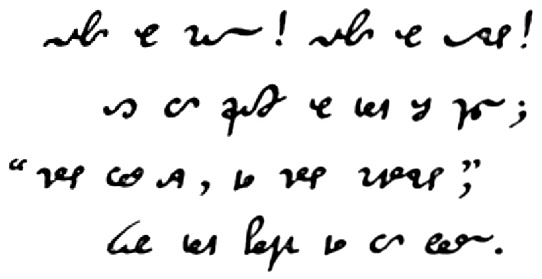

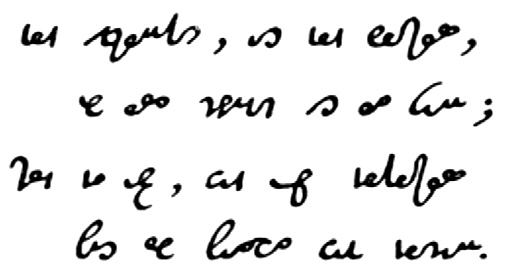

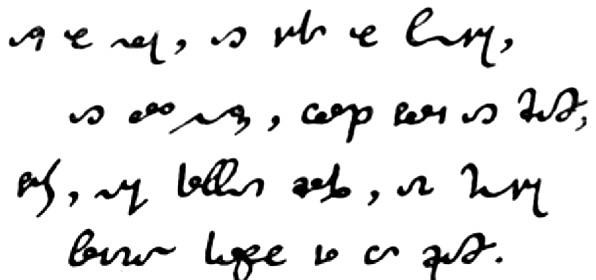

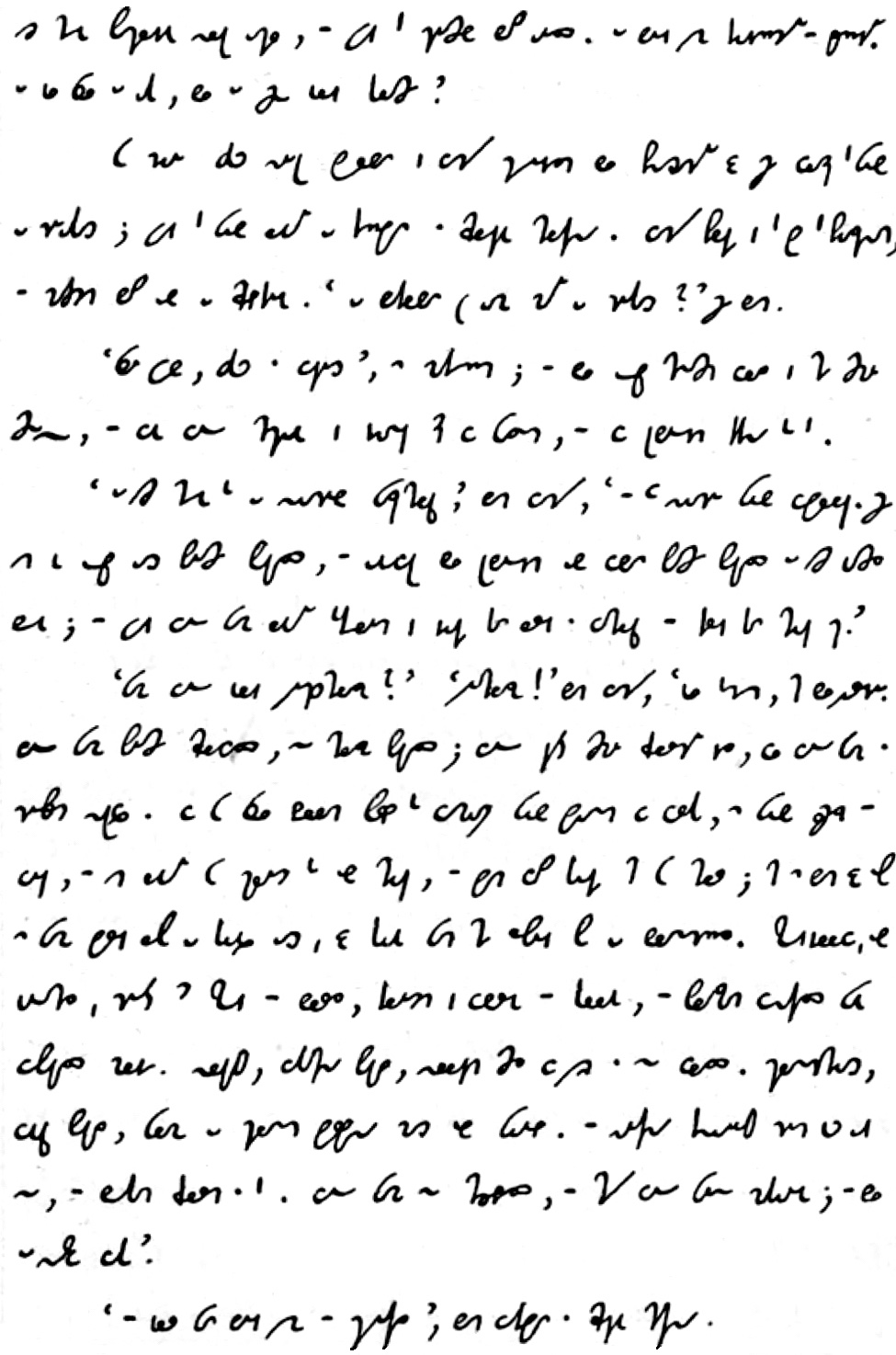

Of the following Specimens the first only is written in full, without any contractions. The first three Specimens are accompanied with transliterations.

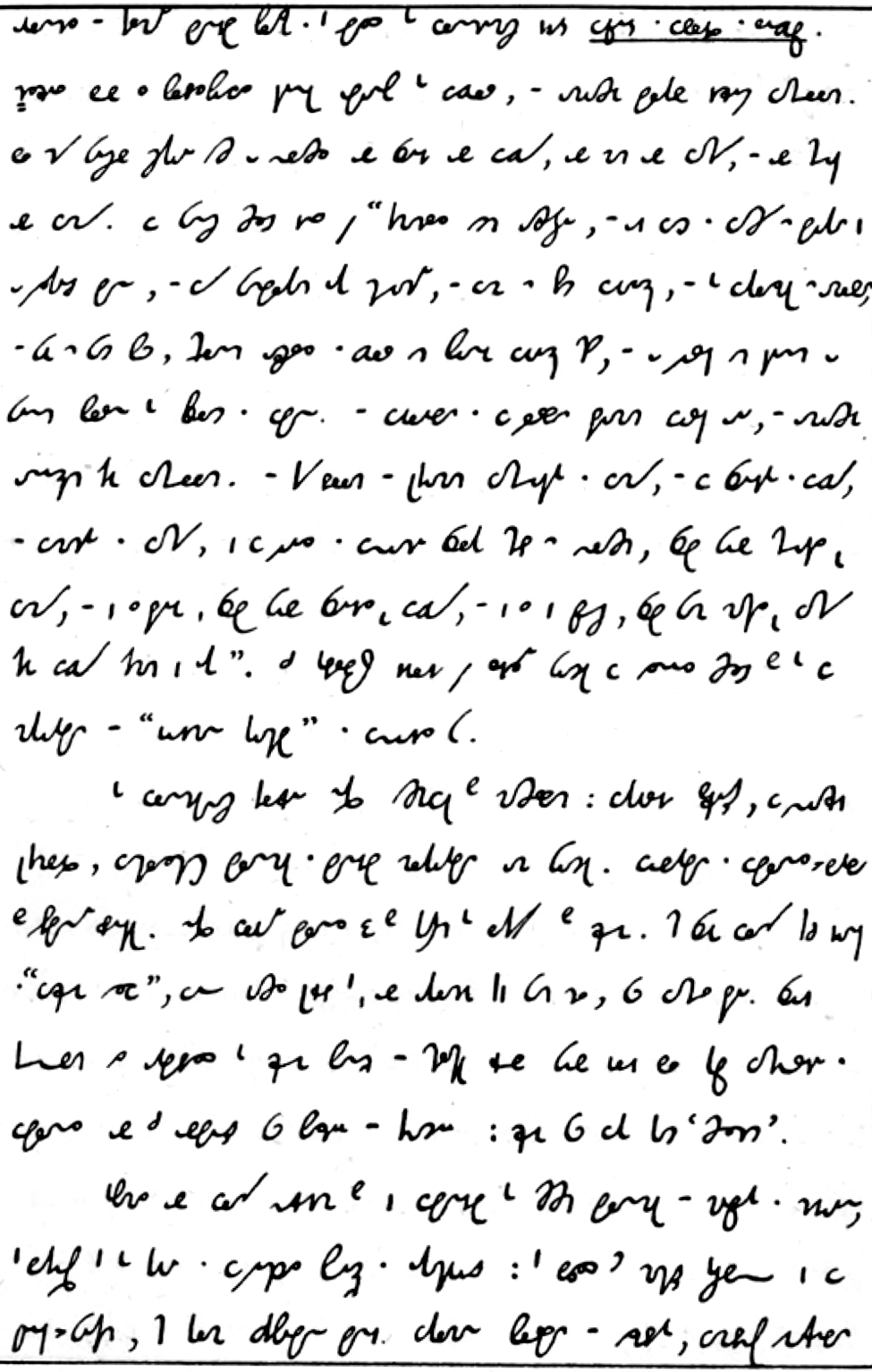

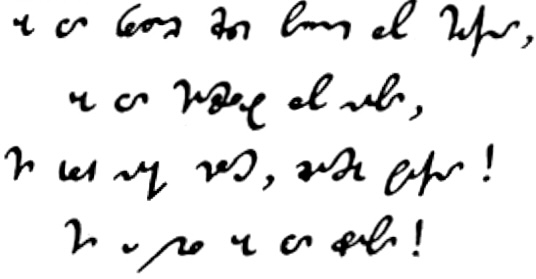

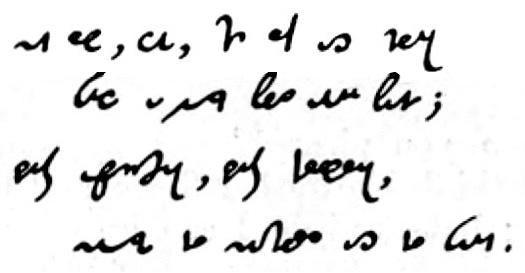

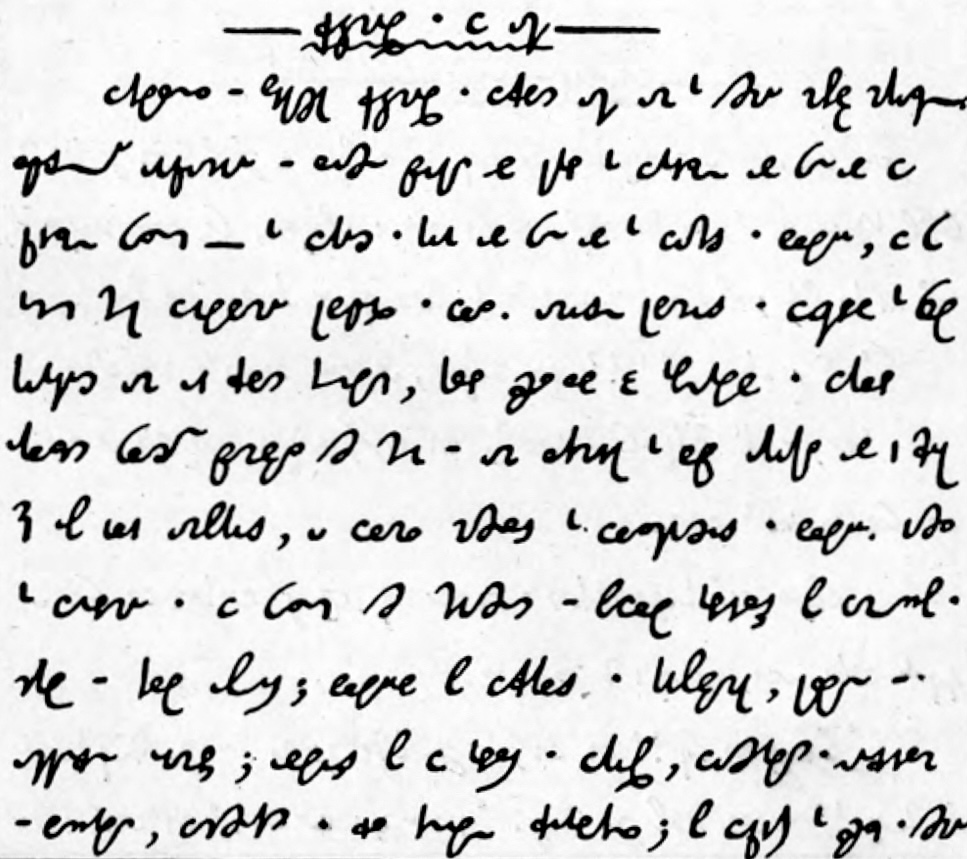

A Psalm of Life

Tell me not, in mournful numbers,

“Life is but an empty dream!”

for the soul is dead that slumbers,

and things are not what they seem.

Life is real! life is earnest!

and the grave is not its goal;

“dust thou art, to dust returnest,”

was not spoken to the soul.

Not enjoyment, and not sorrow,

is our designed end or way;

but to act, that each to-morrow

find us farther than to-day.

Art is long, and time is fleeting,

and our hearts, though stout and brave,

still, like muffled drums, are beating

funeral marches to the grave.

In the world’s broad field of battle,

in the bivouac of life,

be not like dumb, driven cattle!

be a hero in the strife!

Trust no future, howe’er pleasant!

let the dead past bury its dead!

act — act in the living present!

heart within, and God o’erhead!

Lives of great men all remind us,

we can make our lives sublime,

and, departing, leave behind us

footprints on the sands of time;

footprints, that perhaps another,

sailing o’er life’s solemn main,

a forlorn and shipwrecked brother,

seeing, shall take heart again.

Let us, then, be up and doing

with a heart for any fate;

still achieving, still pursuing,

learn to labour and to wait.

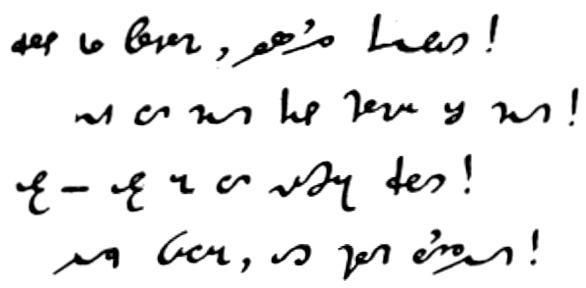

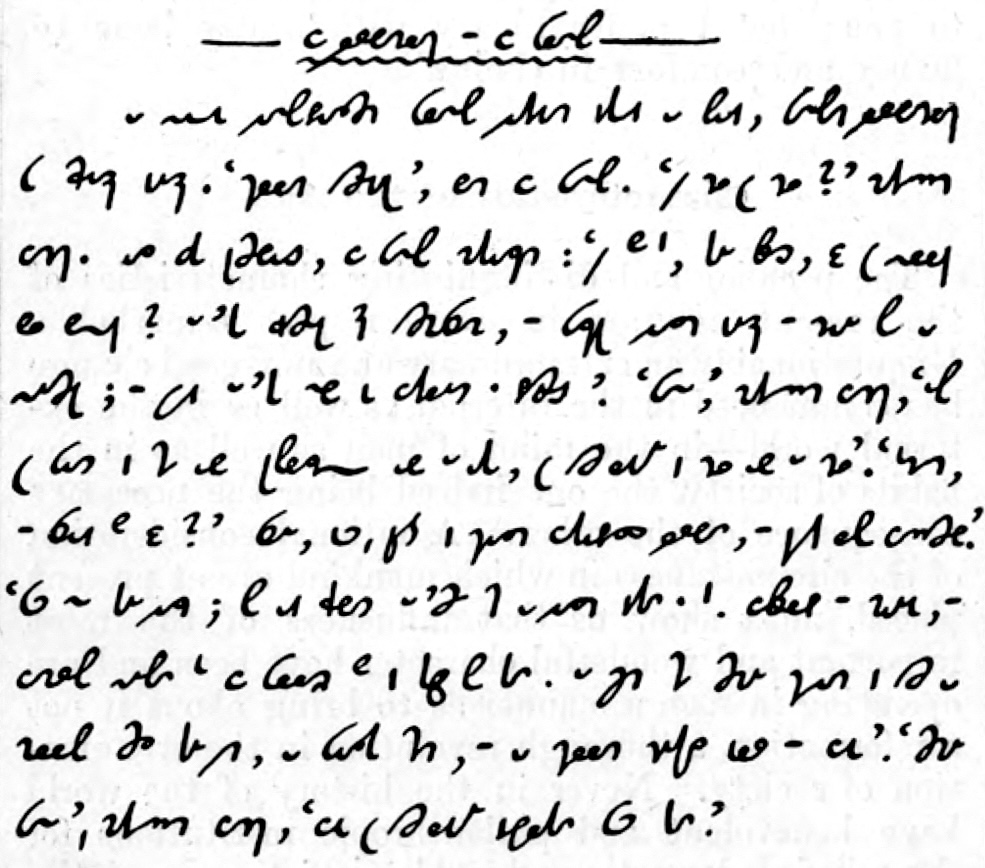

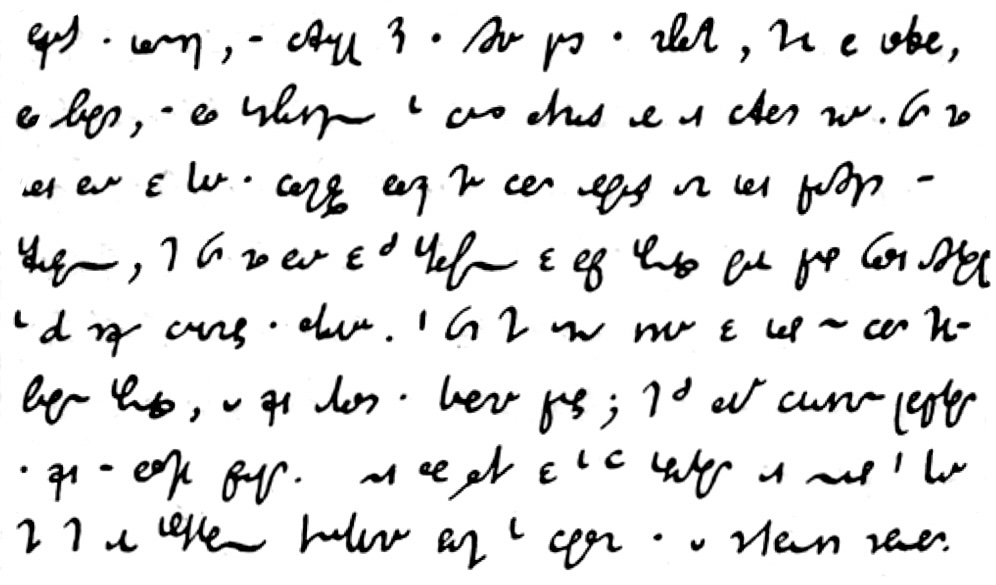

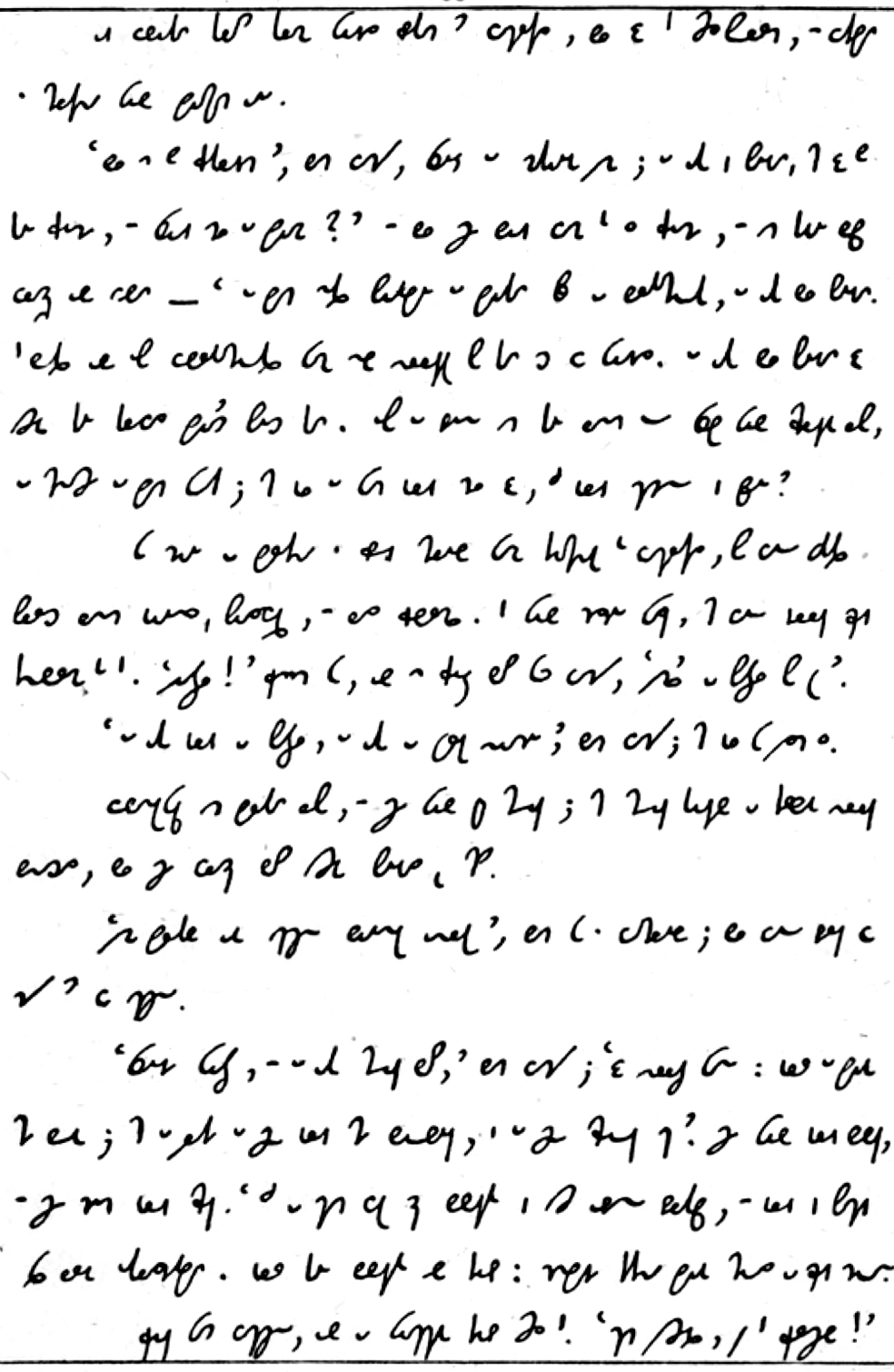

The House-Dog and the Wolf

A lean half-starved wolf happened to meet a fat, well-fed house-dog one bright night. ‘Good evening,’ said the wolf. ‘How do you do?’ replied the dog. After some conversation, the wolf remarked: ‘How is it, my friend, that you look so sleek? I’m travelling about everywhere, and working hard night and day for a living, and yet I’m always on the point of starvation.’ ‘Well,’ replied the dog, if you want to be as comfortable as I am, you have only to do as I do.’ ‘Indeed, and what is that?’ ‘Why, nothing, except to guard the master’s house, and keep off thieves.’ ‘With all my heart; for at present I’ve but a hard time of it. The frost and rain, and the rough life in the woods is too much for me. I should be very glad fo have a roof over my head, a warm bed, and a good dinner now and then?’ ‘Very well,’ replied the dog, ‘then you have only to come with me.’

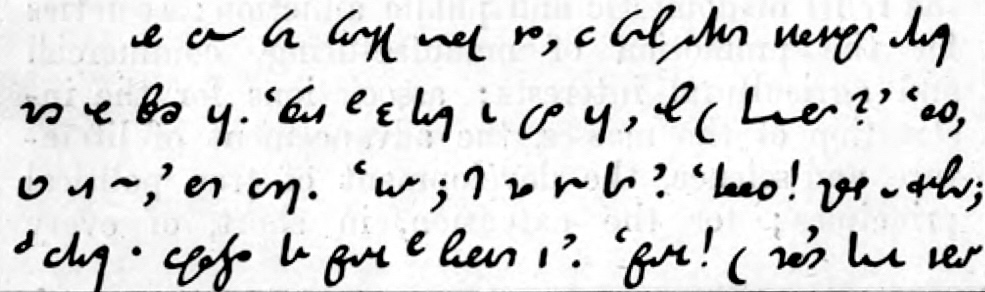

As they were walking along together, the wolf happened to notice a mark round his friend’s neck. ‘What is that mark on your neck, if you please?’ ‘Oh, nothing at all,’ said the dog. ‘Nay; but do tell me.’ ‘Pooh! just a trifle; it is the mark of the collar my chain is fastened to.’ ‘Chain! you don’t mean to say

they chain you up? that you can’t roam about where and when you please?’ ‘Why, not exactly perhaps. They think I’m rather fierce, and tie me up in the daytime; but at night I can go where I like. Then I have all kind of titbits. I get the scraps off my master’s plate; and I’m such a favourite that — but what is the matter? where are you going?’ ‘Good-bye,’ said the wolf, ‘I’m very much obliged to you; but I prefer liberty with a dry bone to luxury and comfort in chains.’

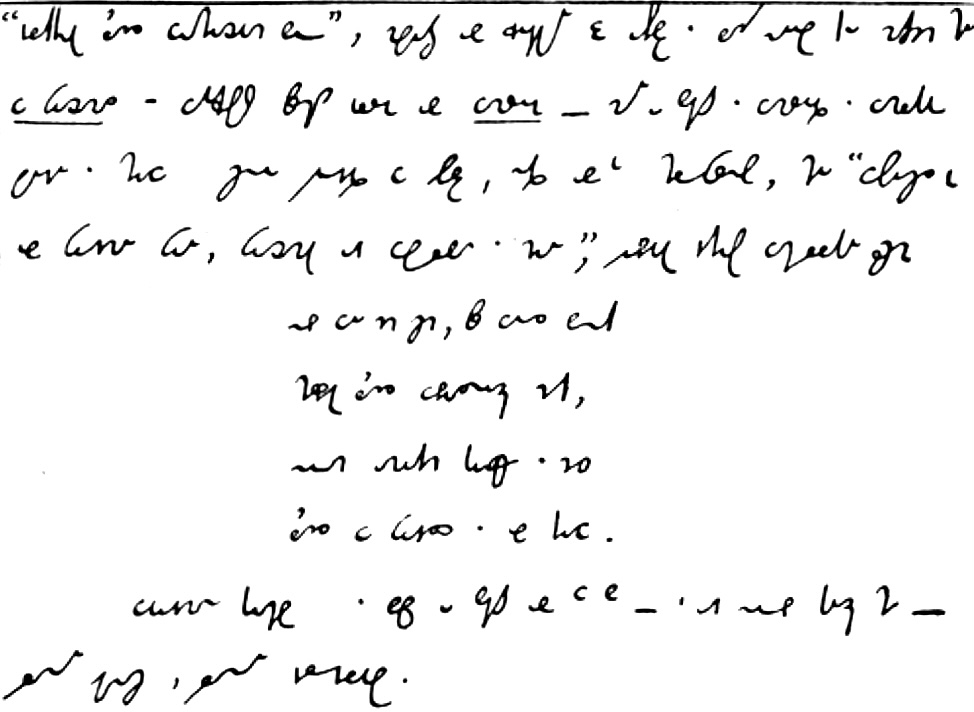

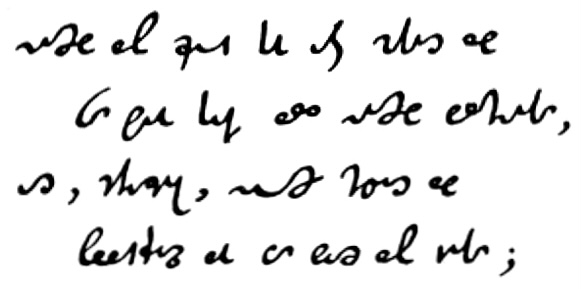

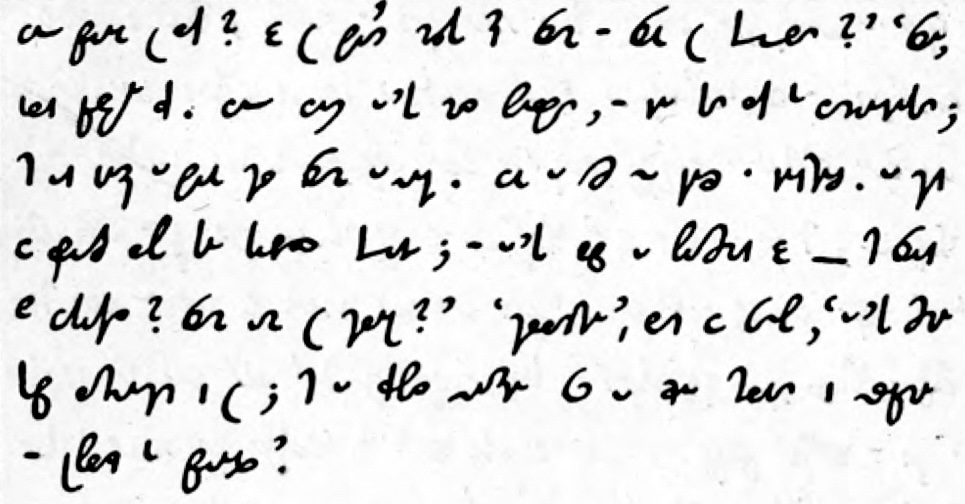

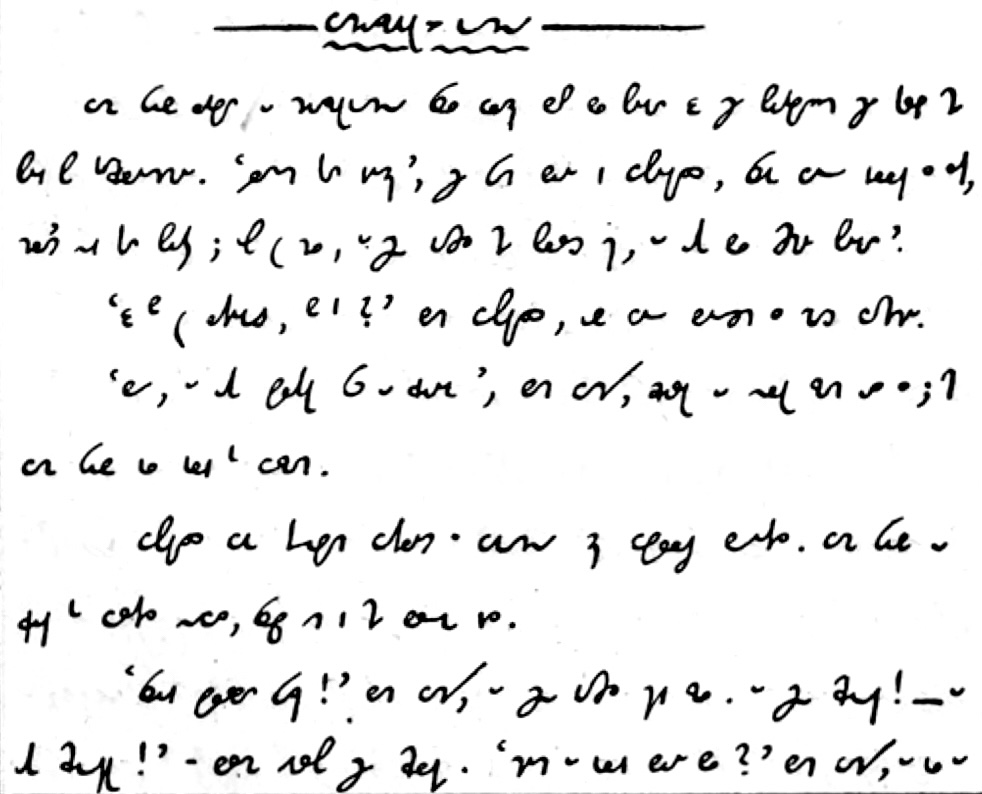

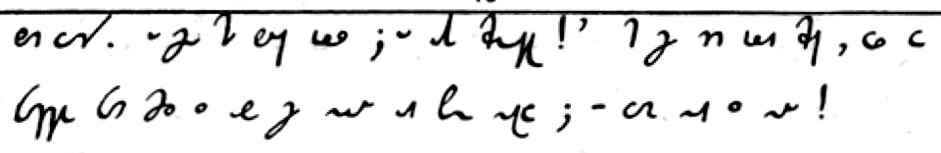

Characteristics of the Age

The peculiar and distinguishing characteristics of the present age are in every respect remarkable. Unquestionably an extraordinary and universal change has commenced in the internal as well as in the external world — in the mind of man as well as in the habits of society, the one indeed being the necessary consequence of the other. A rational consideration of the circumstances in which mankind are at present placed, must show us that influences of the most important and wonderful character have been and are operating in such a manner as to bring about if not a reformation, a thorough revolution in the organization of society. Never in the history of the world have benevolent and philanthropic institutions for the relief of domestic and public affliction; societies for the promotion of manufacturing, commercial and agricultural interests; associations for the instruction of the masses, the advancement of literature and science, the development of true political principles; for the extension, in short, of every

[Here the transcription abruptly ends, though the specimen continues for another half a page.]

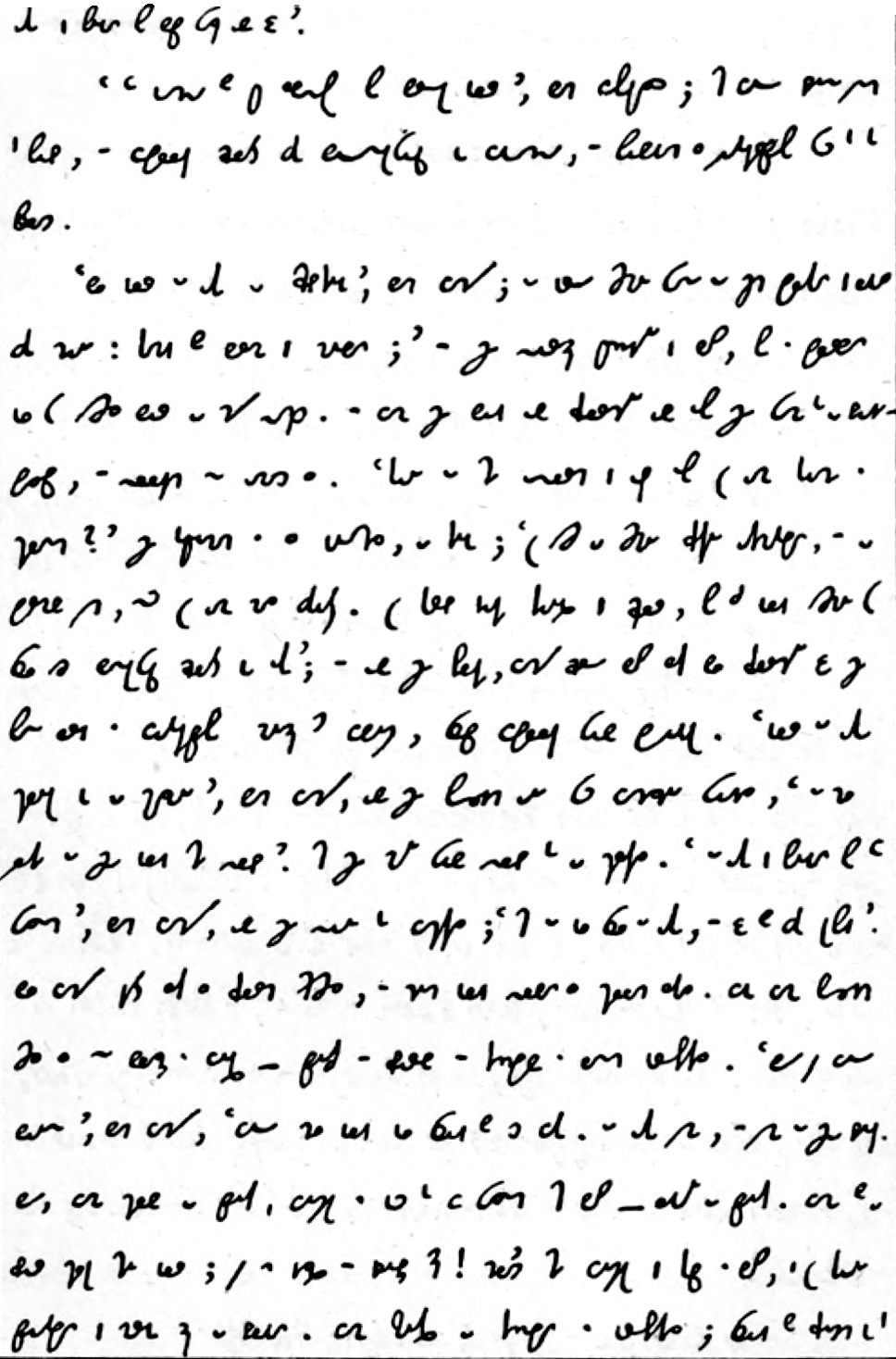

The Darning-Needle

Celtic and Old English Literature